Samarkand, July 15, 2004

In 1913 the poet James Elroy Flecker (who? Beats the heck out of me!) penned the following lines:

We travel not for trafficking alone,

By hotter winds our fiery hearts are fanned.

For lust of knowing what should not be know

We take the Golden Road to Samarkand.

I would like to propose the following modification:

We travel not by asphalt roads alone,

By rougher tracks our backsides are tanned.

For lust of seeing Timur’s majolica domes

We ride the Broken Road to Samarkand.

I left Dushanbe on Saturday, still without my Turkmen visa. Supposedly it will be ready in the Turkmen embassy in Tashkent, but I have my doubts, as the Turkmens seem unable to organize a piss-up in a brewery. Gritting my teeth with annoyance, I rode out of town at 4 pm, racing uphill on the best road in Tajikistan (not a hard title to win) along a picturesque gorge lined by hotels and restaurants—where were they when I needed them in the Pamirs? I spent the night 40 km out of town, lulled to sleep by rushing water.

The next morning I was up betimes to tackle the last major pass of the trip, at least until I get near Teheran. The Anzob Pass, 3350 metres above sea level and 2500 metres above Dushanbe, crosses the Fan Mountains north of town in a 17-kilometre series of switchbacks that looks a wee bit daunting from below. Luckily my legs felt fresh after three days of eating copiously and not cycling, and I got over with far fewer problems than I’d had on the Khuderabot Pass a week earlier. The scenery was wonderful, a series of glaciated Alp-like peaks spreading to the horizon in both directions. Passing picknickers would stop to feed me, and I got to the top feeling only moderately tired and hungry.

From then on the road deteriorated to usual Tajik standards, but, unlike in the Pamirs, as the road worsened, the people did not rise to heights of hospitality. I was royally ripped off at a roadside restaurant, costing me nearly all my remaining Tajik currency, and I pitched my tent in the dark that night in a foul mood.

The next day’s riding did little to improve my temper, as the road roller-coastered up and down between irrigated oases and, on a smaller scale, between colossal potholes. It was frustrating riding, but at least the views provided compensation. It reminded me a bit of the Karakoram Highway in northern Pakistan, verdant villages separated by sterile stretches of desert gorge. I fought my way south to Ayni, and then continued the struggle a further 30 kilometres before giving up and camping in a lovely orchard. I usually try to avoid being seen pitching my tent, and I thought I’d been successful in getting off the road unnoticed, but soon a party of annoying children arrived to disabuse me of this conceit. They stayed at a distance and spent a couple of hours whistling, catcalling and, very occasionally, lobbing a tentative rock towards me. Finally, just as I was about to turn in, two bigger, braver boys came close enough to talk and discovered that I was not an ogre. It was tough to talk to them; this part of Tajikistan seems to have given up on teaching Russian entirely in school, so I couldn’t speak to anyone under the age of 30. Or maybe, since all you have to do to pass school is to bribe the teacher, the teacher had simply passed everyone regardless of whether they had even a slight knowledge of the old colonial language.

The next day I was still 90 kilometres from the Uzbek border, and given the state of the road, I thought that making it to the border would be a pretty ambitious target. By lunchtime, as I had covered a measly 22 kilometres, I had my doubts about even making it that far, especially as the skies opened in a series of torrential, blinding downpours. (I just read on the Internet that these rains completely washed out the Dushanbe-Ayni road I had just traversed; I made it through just in time, as apparently it will take a couple of weeks to re-open the route.) And then a miracle occurred; suddenly, unseen amidst the rain, the valley opened up into a flat, fertile plain and the road returned to a state of near-continuous asphalt. I rode hard to keep warm in the rain, and before I knew it I was in Penjikent, the last town in Tajikistan. I wanted to stop and see the ruins of the old Sogdian town, but nobody in Penjikent seemed to know where it was. Finally, several people told me that it was nearly at the border, some 20 kilometres out of town. I sped along the road, propelled by a huge tailwind, only to find that the ruins there were insignificant Bronze Age excavations and that the city I wanted was back in Penjikent. I gave it up as not meant to happen and raced to the border crossing.

It took a while to exit Tajikistan and enter Uzbekistan. First the Tajik border official wanted to collect a “bicycle tax”. When I mentioned that the Norwegian and Spanish cyclists I had met a week earlier had been told the same but hadn’t paid in the end (because there is no such “tax”; it’s just a scam by the border guards), the customs man got huffy and took me to see the chief customs inspector. The chief shook my hand and wished me a good journey, and when I looked around, the scam artist had already fled back to his office and closed the door. So much for the “bicycle tax”. The Uzbeks were more devious; after I had completed formalities, I asked about changing money, and was told that there was no bank or exchange office at the border, but that they could change some dollars for me. Anticipating a poor rate, I changed only $20, but without knowing the proper rate, I ended up only getting half as many Uzbek sum as I should have, as I discovered when I went to buy a chocolate bar on the Uzbek side.

The sun was still in the sky when I crossed the border, and the wind was still howling at my back, so I decided to make a run for Samarkand. I flew along at 35 km/h until it got dark, 10 km from town. There was more asphalt in that stretch than I had seen in all of Tajikistan, and it was flat. There were shops, restaurants and private cars everywhere, a far cry from Tajikistan, and almost overwhelming after a month in the wilderness. The last 10 kilometres into town in the pitch darkness took forever, as did finding the hotel where I had reservations. (I had to reserve 3 nights at a hotel in order to get a letter of invitation for my Uzbek visa; another official scam.) It took two hours to find the hotel, since not a single person had ever heard of the Kamila Hotel. Eventually I was directed to the better known Malika (everyone assumed I had just gotten the name mixed up) and they phoned the Kamila to come collect a lost traveller. I was happy to climb into a hot shower (!?!) after a 145-km day.

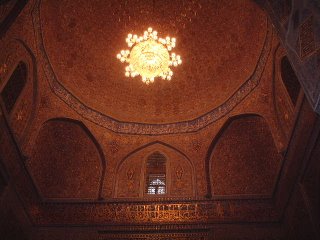

The last two days have been spent wandering the streets of Samarkand in sensory overload. The city is full of medieval mosques, tombs and medressas from the glory days of Timur and his successors, when Samarkand was one of the greatest cities on earth. Huge domes covered in shimmering blue tiles top vast buildings which, over the course of time and numerous earthquakes, have tilted at various subtle angles. The detail of the tilework is amazing, and I took about 4 rolls of slides. I particularly liked the street of tombs known as the Shahr-i-Zindah, much smaller, finer and more intimate than the overwhelming scale of the big public buildings. Today’s photography was restricted by the fact that, once again, it was pouring rain in the middle of the desert. I’ve been told that this has been the coldest, wettest summer anyone here can remember. Global climate change, anyone? At least it’s not as brain-bakingly hot as it usually is, making cycling an easier task. As well, since it’s not too hot, I don’t get too annoyed at the endless stream of begging kids, touts and rip-off artists that surround tourists here like flies. It’s been a while since I’ve been in a real tourist-trap area like this, and I’d forgotten how annoying such folk can be. It brings back memories of India or Egypt.

Tomorrow I’m off towards Bukhara, the second great medieval city of Uzbekistan. With any luck and good roads, I should be able to make the 300 kilometres in two long days. Then a couple more days of sightseeing and an annoying jaunt by train or air to the capital, Tashkent, and the Turkmen embassy to pick up (insh’Allah!) my transit visa, and maybe a flying visit (literally) to the final element of the medieval Uzbek Trinity, Khiva, before heading pell-mell towards Iran. I hope that I’m not stopped by floods or broken bits of bicycle, as I can’t really afford much in the way of delays until I get to Iran; my visa there is only good until July 28th, which is rapidly approaching.

By the way, some of you might be interested in the other side of Uzbekistan, the bit that’s not medieval beauty. Check out this link:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/g2/story/0,3604,1261480,00.html

Hope everyone’s having fun and taking advantage of summer. (That is, if it’s not raining where you are, too!)

Cheers

Graydon